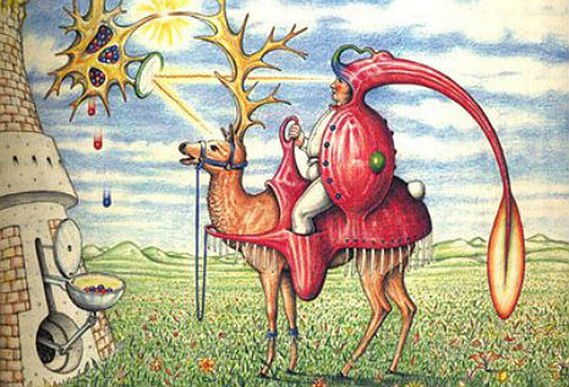

The day had barely hauled free of the dismal, unfledged light of dawn, though noon had come and gone, kept cool and dripping by a hidden sun. Rain had redoubled the weary porters’ burdens, the milky clay beneath their feet a greasy quagmire in which they slipped and stumbled, crying out and clasping one another against the prospect of a fall. Kala'amātya had passed through the belly of Guangxi once before, though on that occasion he had been unencumbered by a small army of inagile companions. The crowded, jewel-green mountains lost their heads in pewter clouds, looking as though they had been flung down from the sky and buried waist deep in the rock beneath. Misted gorges echoed with the roar of hidden torrents that wound between the cliffs; he frowned as the palanquin was set down, and one of its bearers shouldered his way toward him, water spilling from the wide brim of his hat.

“Lord... the lady asks that we rest now.” the bearer informed him, panting as he bowed his head. “She says she can go no further.”

“Tell her that she must.” he muttered, urging his mount onward. Another backward glance informed him that the troupe had settled on the track, adopting the stationary palanquin as a warrant for the unscheduled respite. The bearers crouched by the lip of the precipice, seeking the shelter of its eaves. Porters set down their chests and bundles and took out packages of sticky, leaf-wrapped rice, cramming the grain into their mouths while glancing anxiously toward him. He drew his staff of heavy ju wood from his horse’s harness and slid down from the saddle, striding back toward the delinquents.

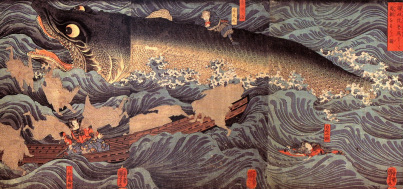

A shudder rippled in the ground beneath him a moment before the advent of a deep, resounding crack that ripped through sodden earth and air. His eyes turned instinctively toward the sky but no bolt had crashed down from the dismal heavens; instead, the puggy trail bowed, sagged, and began to disintegrate, crumbling as the rock below sloughed away from the hillside into a sucking, grinding cataclysm. It drowned its victims’ cries as it bore them down the flank of the mountain, crushing them into the savage mass of trees and stone and earth that flowed like water into the mist, toward a unseen valley floor. Kala'amātya grasped the overhanging branches of a stunted tree, anticipating the imminent failure of his own footing, but was spared; the ground beneath him had broken with the massive wedge that had slid away, their violent dissociation shaping a concave face of clay and freshly-scoured limestone. No more screams drifted upward in the beating rain though he detected a low, keening whimper through the sound of it. Turning his head to assure himself that he was not mistaken, he sought its source below the edge of the surviving trail.

The white palanquin had become wedged on a tangle of broken trees. It lay on its side while a passenger begged for assistance from within. Wiping the rain from his face, Kala'amātya walked out along the remaining track and swung down onto the shorn stone of the cliff face, sliding on his haunches toward the pinioned vehicle until he attained its supporting ledge. A wrinkled matron’s face, flat-featured and high-browed, appeared from behind the chair’s spattered drapery; she exclaimed at his approach, praising the gods that had flung her entourage to their deaths for their judicious lenity while he lifted her from her frame and set her down onto the crumbling ledge beside him. The chair's remaining occupant, having lost her grasp upon the uppermost door, dropped down through the wooden framing toward the opposing one, now yawning out over the drop. Her bare feet had already passed through it into the empty air when his fist closed on the fabric of her robe and took her weight, slamming his arm against the cracking timber. He dragged her back up through the drapes onto the ledge.

Delivering them to the safety of the stable ground proved less difficult than he had imagined. The elderly matron, having no wish to join her ancestors, scrambled up onto the road with remarkable, almost pithecoid alacrity. The younger passenger climbed before him, independent of his aid; despite the station implied by the cargo that had attended her, she wore a plain, stone-white kimono of humble cloth and plicated amplitude. Her black hair hung in a tangle of broken combs beneath her hood. She sank to her knees on the edge of the trail and looking down, he saw the features of the girl who had brought the lilies to his barrack hut. The matron abandoned her own cursory toilet and scolded them.

“This is my mother’s sister.” Suki murmured. “She has no sight.” He took the cue from her formality and abjured mention of her name.

Shuffling toward him the older woman reached up with both hands and attempted a manual survey of his features, only to be thwarted by the great discrepancy in their statures. She scowled more deeply at this discovery and groped downward, following his arm to his hand where a count of his cool fingers caused her to fling it down and stumble backward in disgust.

“It is you, the kyuketsuki, the oni... you have tricked us into this misfortune and now you mean to devour us!” she exclaimed. The matron at once began to chant, crouching and devoting herself to pious defence against his peril. His horse returned, blowing snorting breaths at the small party of survivors.

“This creature has saved us both from falling." the girl advised. "He means no harm.”

“Because it has already satisfied itself in wickedness!”

“Stay here then, with the virtuous spirits of the wood.” she sighed.

Kala'amātya caught the loitering horse and beckoned to the pair; the old woman squinted obstinately as her niece explained his proposal, which she treated as an affront to the manners accrued in a lifetime of sheltered luxury, the pitch of her objections ascending as he lifted her into the saddle. The girl shook her head against the prospect on her own behalf, her insistence intensifying as he approached her. Catching her arm, he pushed his hand into the fold of her robe, setting it against her stomach; her gaze rose to his as he perceived the gravid proportions the fabric disguised, attained in the three months since their last encounter. The old woman pressed her dry, penurious lips together as her ward climbed slowly into the saddle before her.

“Does it please you, to have begotten evil on this girl?” the crone snapped. “No matter. She is made of wickedness, and if the paint were scrubbed from her face you would find the mark of it there, where she has devoted herself to witchcraft, to compound her crimes.”

“You are mistaken.” he told her. “I have no part in this.”

“Though they come from all around to eat the fruit, none will own that they have planted seed. Thus it was in my day, and so it is in hers. The palace guards have followed her to your house and back again, a dozen times!”

“Tokogawa himself has done the same.” Kala'amātya replied. The rationale enraged her.

“Tokogawa does not lie with demons when he is betrothed to a family beyond reproach... he has not disgraced himself with a dozen nameless lovers in Kyoto! Nor consorted with the tsukimono-suji, and consigned himself to hell.” Recovering, the old woman sought the composure she cherished most, speaking with the cool, serrated assurance of her station. “If you are not the sire of this accursed child, you are close enough to be so in the eyes of others, and that is the heart of all such matters.”

Kala'amātya did not reply, but murmured to their patient mount, leading them once more along the slippery track as it reached upward into dripping forest.

The evening padded in on tender feet, as still as the boles of the trees lining the path like the distorted figures of a lavender opium dream, the feeble sun setting behind them. The old woman marked Kala'amātya's figure as a tall blur against the darkening ground.

“Why did you travel to Honshu?” she demanded unexpectedly.

“It lies furthest distant from the kingdoms beyond Persia.” he admitted.

“Tokogawa tells the bushi that you were sent to serve him by the gods.”

“Tokogawa may be shogun, but in Edo, I bow only to sword smiths and oiran.”

The woman scoffed, then continued her interrogation over the shoulder of her ward.

“What great evil have you committed that you may not stay where you were made?”

“Many, countless evils. But I shun my brother and his wife... she is lost, he wanders with her, and I can not abide it.” he said, unable to think of any reason to conceal the nature of his misfortune.

“You abandon your brother? Where is your loyalty?”

He shook his head.

“I no longer ask this of myself. You speak of duty, and that is fear of sanction, and my elders in their wisdom ensured I could honour nothing of that nature.”

The crone murmured again at his apostasy.

"In asking nothing of yourself you will be answered in kind, and please them well who wish no more for you. What a wretched thing you are... even the mountain would not take you, and I do not wonder at it."

Nightfall found them at the winged gates of a temple. The low buildings beyond, of dark wood on a darker stone, lay deserted, their yard inundated by the rain, nodding stands of arrow bamboo hemming water in which their reflection was shattered by the horse's hooves. Beneath their eaves the dormitory halls held a deep rubiginous hue, the colour thickening the gloom. Lightning flashed against their backs, gleaming white along the polished walls as Kala'amātya followed them into shelter, his cold skin crawling in the still, charged air. He guessed that flood and landslides had kept the temple’s order from returning to their home and the rendezvous they had contracted with the shogun.

Peering fruitlessly into the darkness, the old woman flinched at the clapping of iron-shod hooves against the floorboards; ignoring her complaints, Kala'amātya removed his kit and saddle from the personable equine’s back and directed the animal toward the corner furthest from the door, where it nodded to sleep on three hooves. Heat from its damp flanks soon warmed the chamber and the matron quit her grumbling dissent, sitting with the girl, who had slumped against the wall beside the door. He arranged his blades and naginata on the boards and began to unlace his armour.

“I did not know who I brought to this place.” he confessed to the girl as she watched him.

“What does it matter now?” she murmured.

“Thus speaks the great favourite of a great man.” declared the matron. “Nor did you think of right and wrong before you were undone.”

“Tokogawa required that I take this chair into Cataya and leave it at this temple. This I have done.” The matron made no reply, kneeling by the wall, her white hair fraying from the side of her chignon and falling, unheeded, before her milky eyes. “It is my thought that he has charged you with further instruction, honourable mother.” Kala'amātya added. She maintained her obmutescence and he looked around at the sound of the girl’s breathing, her smooth face creasing with the effort of concealing the unwelcome rhythm that had obviously begun some time before. Wind slammed the unfastened door against its frame; the horse squealed, and the girl turned toward him when he knelt beside her.

“You will leave now!” the old woman exclaimed on perceiving her condition.

“You are blind.” he reminded her.

“You are a demon!” she retorted, stiffening as she raised her voice above the wind. The girl reached down through her robe, withdrawing a hand that brought with it the sharp, dusty smell of amniotic fluid, stained a deep tea-brown. She looked up at him.

“I know you can bring children forth..." she gasped. "You aided Umi, and Fumiko’s sister... this child does not fare well...” Again he lay his hand against her body, the infant's distress beating through its mother's flesh, a desperate petition.

“It does not.” he conceded.

Despite the dire interdicts of his own people, long association had drawn him into intimate familiarity with feminine ordeals, compelling him to deliver the diverse issue of bandit girls and seige-bound chatelaines into their uncertain tenures. The cascade of signs and processes and the timbre of the girl’s exhausted screams were by no means unfamiliar, though he rued their implications along with her aunt’s unrelenting pessimism. The infant would not emerge though the girl had striven on her haunches until her brown eyes rolled into her head and her sweat-slick arms slid through his hands as she slumped back in agony and despair. He eased her legs from beneath her through the thickening pool of blood into which she had collapsed, bundling her discarded robe under her head and draping her with his own. Her stomach was tight and coldly slippery beneath his hands, devoid of movement; the matron shuffled closer on her knees, repeated the inquiring gesture and sat back.

“Better that they both should perish. Misfortune will follow them always.” she assured him, her dry voice weighted with puissant finality. "Leave her to her fate." She pressed a narrow scroll on him; the cylinder was still faintly warm, drawn from somewhere in her robe, and inscribed with the shogun’s seal. He set the missive aside and returned to the half-insensate girl.

"Suki, if you do not labour now, I must use my knife to bring it forth, and that fails more often than it succeeds.” he advised, kneeling by her shoulder and ensuring that she understood. At her word he drew her back onto her haunches, taking her weight with both arms and legs as she set her back against him and closed her hands upon his wrists, her chaperone expressing in vehement terms the abdication of her familial commitments.

C O N T I N U E D N E X T W E E K

© céili o'keefe do not reproduce

RSS Feed

RSS Feed