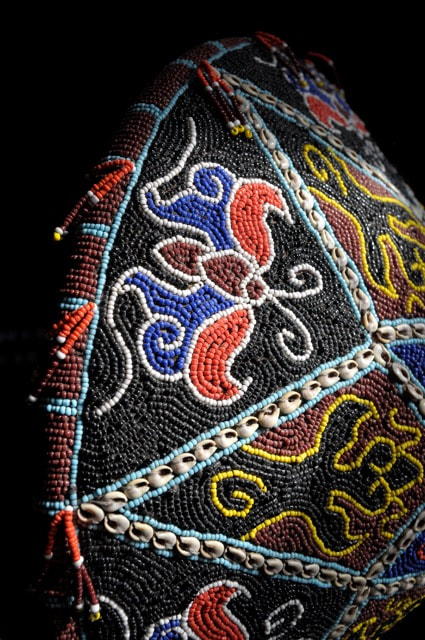

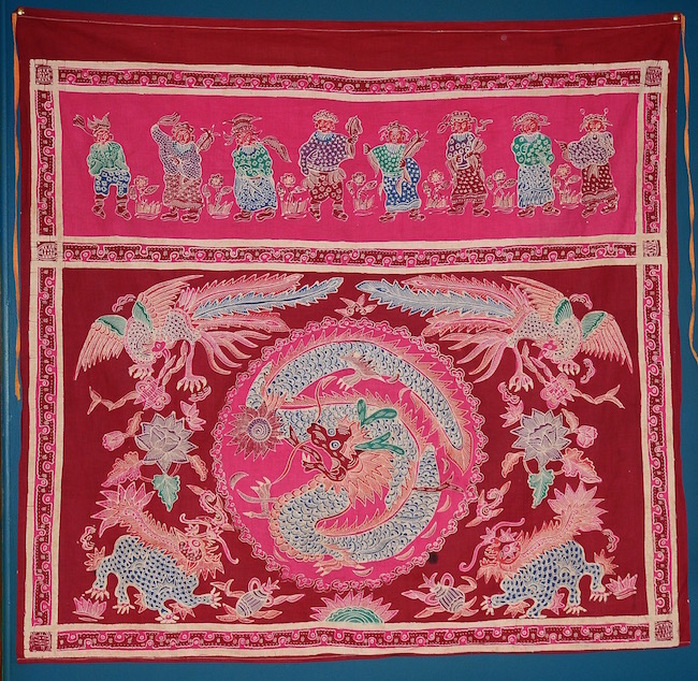

Anyway, I had this feeling a couple of weeks back when I spotted this large and incredibly beady conical item. I didn't know what it was, exactly, but I did know that it was one of those awesome and poorly-described things that must be mine. Lucky we still had double figures in our account!

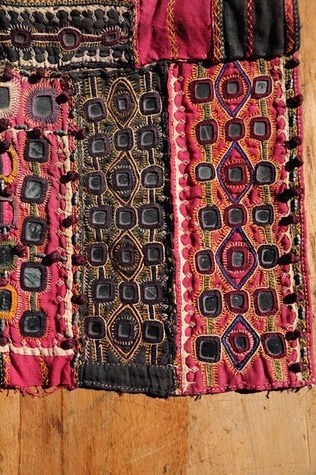

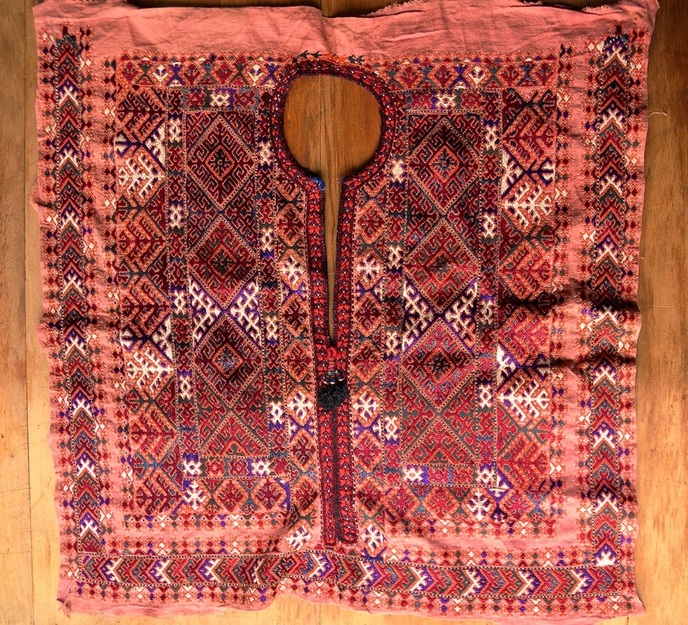

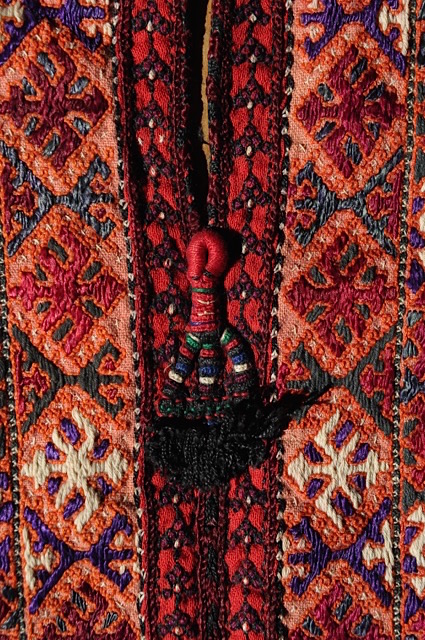

On one level it is intensely depressing to find these beautiful heirloom pieces and know the incredible aesthetic traditions they represent are falling into redundancy. But what can you do? Collect and value them, I suppose, and try to attribute them correctly.

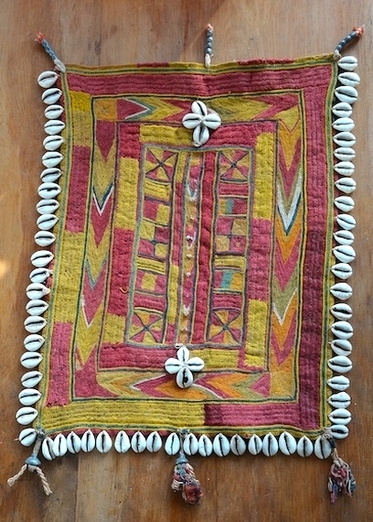

| The cover is rigid and heavy, as you can probably imagine, and greasily lustrous. Beaded work can be hard to date definitively, possessing qualities that confound the usual indicators of age. Old beads can look surprisingly modern because their pigments don't fade and vintage work can be repurposed and applied to contemporary pieces. Some of the tiniest and indisputably earliest trade beads used in the oldest extant Indonesian/Malay pieces have been unpicked and incorporated into much later items. And tropical usage can be hard on the underlying organic fibres, resulting in wear and patination that can overstate an item's antiquity. So I personally take all bead-related age statements with a truck-sized grain of salt. Who knows how old this cover is? It is in excellent condition with no visible losses, but that is not too surprising since they were apparently heirloom items that were probably treated and stored accordingly. |

Dealers are pricing these covers out of our modest reach so it's gratifying to hear that they still turn up, misidentified, on Ebay occasionally where they represent a lot of ethnographic and artistic bang for your buck. I bought this one from a lady who used to live in Malaysia and consider it one of the greatest bargains I've ever stumbled across.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed