The Banjara (or Lambadi/Lamani) people are a formerly nomadic tribe, largely (sometimes nominally) Hindu, distributed across India and are one of the putative ancestors of the Roma populations scattered throughout Europe. They've suffered their share of the socioeconomic disadvantages incurred by virtually all traditionally mobile groups compelled by policy and circumstance to take up subsistence agriculture, but seem to have retained a distinct identity.

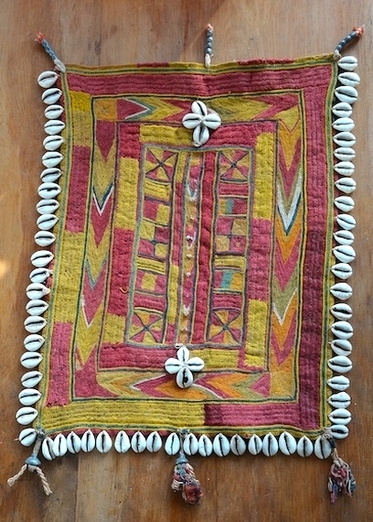

It's safe to say they enjoy ornamentation. To my dilettante eye, their aesthetic has a lot in common with that of other designated 'tinker/gypsy' (I find these terms borderline derogatory but they have wide historical currency) and dissenter groups across India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and into Central Asia such as the Kutchi, Kalashi and Baluch. It rejoices in the vivid hues and massed amulet devices of fortune and protection and declarations of portable wealth.

Settlement seems to instigate a pattern of divestment familiar to any collector of ethnographic textiles. The stuff that Nana wore loses its relevance as the cultural context is lost; these pieces are sold to traders who then move them on to tourists and western collectors. While this may seem a melancholy reality, in practise it has resulted in the preservation of a lot of wonderful material. I bought a collection of really nice vintage textiles from a lady who'd spent time in India, Pakistan and Afghanistan, getting to know the locals and being gifted old family items as tokens of appreciation for the work she was doing. These two pieces are the first from that group that I've posted so far.

| It retains most of its original ragged tassels (see details below) and even the soft lead beads that decorate them. From the tufts of white thread in the central band I guess it might have lost a line of cowries there. The chain stitching is incredibly dense, covering every nanometre of the underlying structure, every cotton thread spun and loomed by hand before being worked to this glorious extent. A cursory investigation of the interweb leads me to believe this piece is from Karnataka (formerly Mysore), as the style and technique is characteristic of that region. I'll stick my neck out and say it's from the first third of the 20Cth. There's not an artificial thread on it, the colours are vegetable-derived and have that almost indefinable patina of both wear and age. Dating handspun cotton can be difficult since these materials and techniques were used until very recently throughout Asia; you can encounter pieces separated by a century that are hard for the beginner to differentiate. But once you've handled a decent number of pieces even the novice can start to get a feel for relative vintages. |

| We don't view the use of synthetic dyes as an aesthetic catastrophe, but we're a minority among collectors who have historically been obsessed with excluding anything containing them from personal or scholarly appreciation. Rug snobs are the worst, but hey- we're happy to pick up the awesome pieces they've discounted because of a single colour. In both of these pieces the cotton thread and backing cloth is visibly hand-spun and hand-loomed, full of natural irregularities and possessing a soft, rubbed, weary sort of dryness, factors that reliably denote age in the absence of provenance. More recent cotton is smoother, waxier in its finish, has a tighter handle and tends to be synthetically coloured (though this is not always so.) Modern embroideries tend also to be 'neater', more determinedly symmetrical and less idiosyncratic in their design. The stitching itself is almost always larger, coarser and more cursory looking, particularly in items produced specifically for sale rather than personal or dowery use, though elements of the design might still be perfectly ancient. The 'arrow' or directional bands to each side of the above piece are a motif used by tribes all the way from Tangiers to the Tonkin Gulf for thousands of years, and are still employed today. | Organic dyes do tend to fade softly and evenly, (although there are a surprising number of corrosive exceptions that will actually destroy the underlying fibres) and inorganic colours are sometimes jarring and less 'harmonious' to the extrinsic eye, but harmony isn't everything, and these considerations were not uppermost in the minds of the various creators. As an artist, I find this distinction spurious. Not to mention sexist, conservative, arbitrary and gobsmackingly arrogant. The same people who'd praise Picasso or Basquiat for using chrome yellow think they know better than the Banjara lady who likes neon pink. (Rant over.) |

| This gala is quite possibly older still than the one above. It's a rather tired old soldier with a few glass losses and no tassels left to speak of, but its enduring beauty and purpose as a protective item could not be more emphatically expressed. It's from a Banjara family in Madhya Pradesh. It features various raised embroidery, appliqué and shisha work, the pieces of handblown glass couched around with sturdy chain stitch. (You can see the reverse directly below) The dusty saffron palette just breathes age, its colours both rich and subdued in contrast to the remains of the replacement stitching in whacky green that once held the ties in place. The shisha glass panels are thick with bubbly irregularities and burnished with a petrol-blue lustre, in contrast to the foil-backed silver mirrors used in contemporary work. They are murky, jewelled phylactery, staring down misfortune and jealousy. Below- rear details. | In the detail below you can make out a number of the techniques employed in this piece. Visible also in the vacant glass apertures is the old plain-weave cloth that forms the basis of this textile, with the exposed stretches only slightly faded in comparison, a factor which also argues for organic-based dyes and an early date in this instance. I really enjoy the spiky bands of appliqué and lively floating thread on this gala. Despite the stiff visual competition that crowds our bedroom, it commands a very special kind of attention, lurking on the black wall like Argos of the hundred eyes and never, ever blinking. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed