The cab driver hooked an arm around the seat beside him and peered down the winding cobbled drive toward the neglected address of her description. The girl sitting in the back of his car checked the ballpoint inscription on her hand.

“Two three one Commoriom Drive... can you see a number?” she asked, scanning the ivy. The driver frowned, her accent dampening his already deficient interest, but the sun dropped a ray over the unmown field beyond the vine-choked palisade, glowing lime-green in the fresh grass and illuming three brass numerals beside the gates.

“There you go, two three one. That’ll be fifty bucks.”

Her mouth dropped open at the price of the fare and she sat for a moment, almost prompted to challenge it before shaking her head to herself, counting out a crumpled ball of notes and dragging her suitcase from the malodorous trunk. One side of the gates swung inward when she shoved hard at the rusted curlicue, voicing a low, drawn-out complaint. The sinuous drive presented signs of habitation; the rubbish bins stood choked with bottles ready for removal and an elderly motor scooter lay on its side in the lawn at the place where the last gasp of air had escaped the front tyre. A pair of black boots crouched in the half-timbered porch, split up the back with some sort of blade, thorny twigs entangled in their laces. Raising her hand to quash a sneeze, she looked around again and depressed the doorbell firmly. A fat green spider lowered itself slowly, paying out a thread of sticky gossamer, ocelli gleaming as the breeze turned it in a circle.

Sparrows declaimed noisily behind her while she waited. Leaving the porch, she peered vainly through dust-dimmed banks of windows to the east; several were cracked in their frames of blackened oak, the wood exuding streaks of copper brown over the lower course of plaster. Back at the door she rang the bell again and hitched up the strap of her bag, its embroidered mirrorwork catching the sun and throwing reflections across the panels surrounding her. Shaking her head, she puffed a sigh and set off across the garden, abandoning her suitcase.

Crushed underfoot, the lawn loosed drifts of sportive moths and gave up a dewy vetiver, the quiet, smoky smell of the sun in its depths cooled by notes of moss and stone exhaled by the trees, their influence like that of blue buried in green. They formed an arboretum to the rear of the colossal pile, crowded with exotic fin-de-siécle beauties purveyed by peripatetic botanists alongside those classic species treasured for their nobility; though untended, it had rejoiced in that very desuetude, forming a trackless and bewilderingly exuberant folly that ran as far as she could see toward the south. Chinese elms threw roan-blue shade across the house, their leaves like rounds cut from the gilt skin of an idol, feathery aruncus and tardy feral tulips clustered underneath, still losing crimson petals to the breeze.

Beyond them she discovered the corner of a relict orchard, valiant, bisque-white blossom still studding the boughs of the decurving pears. She was surprised again by the outline of a parterre in the neighbouring sward, a pool set in its midst and trimmed with blocks of sesame sandstone; it held a foot of rainwater and the leaves of the previous autumn. The sun and the cicadas' seamless chanting pushed her hand into her bag in search of her hat, passerine habitués scolding her intrusion from both sides of the clearing.

Indecision sat her on the low wall at the foot of the parterre and had closed her eyes in the shade of her brim by the time sound began to drift from the orchard toward her. Brushing off her skirt, she walked along the pool and into the fruit trees, pursuing the noises encrypted by the breeze. One overgrown aisle turned into another, crossed with fallen branches and draped with swags of morning glory. The voice came to her again, morphing from softly-mitigated babel into words with a slow rhythm and the suggestion of purpose. She bent down with her hands on her knees and peered beneath the rows, espying two bare feet, their calves and a tattered hem of hand-worked cloth in sober blue and ivory. Their owner stood beneath a pear, murmuring a recitative.

“a’ma, shali, a’nii s’ae kala ae s’ae siithra,

s’ae silya rani ae s’ae jiiani imaanae...

il bai’issan avai’ia e’shii assil nai’iim.”

She squinted through the boughs as she rounded the last tree and beheld the stranger in his entirety. He reached toward a dark shape in the leaves that shifted and thrummed, a delinquent swam of honey bees, which he coaxed onto the piece of branch he held aloft for them. Their warm, gold-soaked drone expressed their conciliatory mood and they came together, persuaded to descend. Lowering the swarm toward himself, he looked to her with wide sloe eyes full of irradiant, dissimilar green, their disparity redoubled by the shadow-dappled sunlight striking them unequally. Something in his face spoke of moderate surprise, which she reflected tenfold.

“Are you... Mr Lamb?” she began uncertainly. “Is this not... a very good time?”

“They’re much happier than they were.” he assured her, referring to the bees. Around his feet a trio of parti-coloured birds pecked busily at the insects that had fallen into the grass, their legs forming a fulcrum between their elaborate tails and pursy bodies. He wedged the branch into a crook.

“I’m sorry...” she murmured. “I must have... are you... Edward Lamb?” She stepped sideways in the midst of her inquiry to avoid the drowsy passage of an insect. Nothing could have persuaded her that he answered to that name.

“No, I’m William. William Lamb.” he smiled, holding out a hand. She stared up, first at the violent sanguine of his hair, then his face, its ice-white, almost specular brilliance agreeing with the coolness of his grasp, like the shade that she had left beneath the elms.

“Susan Christabel.” the girl replied. His features obeyed a severe, disturbing symmetry, their oblique arrangement forming an uneasy accord with the droll set of his mouth. He was as tall as any scion of the Masai or Rendille, though taken together, his conflicting attributes defeated the cartography applied by her subconscious, her uncertainty compounded by his garb and the language that had drifted through the trees. With her hand still in his grasp her gaze followed the breadth of his naked shoulder and descended to the ikat cloth rolled loosely about his hips, frowning again at the insecurity of its careless configuration. Susan reached down into her bag, withdrawing a letter of referral.

William attempted to peruse the document conscientiously though his eyes drifted from the page toward the visitor with a frequency of which he was not entirely conscious. She was of relatively unimpressive stature, but the black pinafore that pinched her at the waist did nothing to disguise her softly-fleshed proportions, nor the watermelon pink flushed over her cheeks by the hot sun. When the breeze drifted toward him it conveyed the scent of her afternoon skin, sandalwood soap and the raspberry croissant that she had eaten in the car. Small silver hoops trimmed her ears and she had removed one from her nose; the hair beneath her fisherman's hat, streaked mottled tortoiseshell by a brush with peroxide, would have lain upon her shoulders if it had not been pinned behind her ears. The document informed him that Opal La Rue had arranged her appointment and he frowned, then smiled remedially, revealing exemplary teeth.

“You’re English?” he inquired. She nodded.

“You?”

“Oh... no.” Suspicion lifted her dark owl eyes, a sable, spotless blue, and he smiled again, referring to her unresolved inquiry. “Burmese.” The word floated, briefly orphaned, until she ascertained that he was referring to himself. "Or Tibetan. I'm not sure. If I'd known you were coming, I would have put on a tie." William returned the letter. The visitor remained unsmiling. “Want to see the house?”

She stared past his shoulder.

“Will they be alright there?”

“Who?”

“The bees.”

He stepped back against the trees to let her past.

“Of course.”

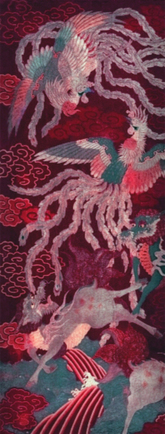

Susan trudged behind her host toward the house, her eyes on the lawn as she weighed her distance from the city, the taxi fare and the possibility of charging it to her agency, and a dozen other practicalities that clamoured for attention. Behind them, the pheasants began to crow in an absent fashion, their efforts to recall him losing out to their preoccupation with their meal. When he spoke again she looked up, and was confronted for the first time by a great expanse of blackline figures sprawling from two points low down on his hips and devouring the surface of his back and shoulders. It was composed of wild, interfluent zoomorphisms in an arrangement more insistent than disorder but less immediately gratifying than any elegant literal schematic, elements merging and yet retaining independence. Dotted points of the same dark colour followed their outlines like diacritic glyphs, the whole composition raised and uniformly scarified. Two answering forms, transfigured beast’s heads garlanded with spirals, spilled down the backs of his arms and reached halfway to his elbows. She closed her mouth to prevent the escape of any exclamation.

“Pool.” William told her as they passed it. “Don’t worry, I’m working on it. House... it's, er... vintage...” He led her up to a pair of French doors in the rear wall, densely swagged with overgrown clematis, its simple musk-pink buds opening almost shyly. "Are you superstitious?" She shook her head, then nodded; he reached up into the vine and tapped the lintel buried beneath, uttering three words in the language that had drawn her to the orchard. Susan stepped inside at the behest of his smile.

They climbed up into a cavernously dark and previously formal drawing room centred on a hearth tiled with satiny, striated malachite. The boards creaked under an elderly Kurdish palace carpet soaked in the precious jannah colours of a weaver's fondest dreams, and this single item had been deemed sufficient ornamentation. Its walls retained their sombre Jacobean panelling, but as they continued into the hall beyond the deep green paper over the wainscoting sagged with the failure of the underlying plaster and the ceiling began to litter the floor intermittently, revealing the roof’s decay. Rugs lay rolled against the skirtings alongside massive gilt and gesso frames. They detoured into a kitchen tucked behind the front door, originally some capacious form of cloak room; William smiled with perverse pride at the red pearlescent formica and blanc et noir linoleum of its conversion.

“People say that on that dark night in fifty-three, thirteen psychotic stenographers took their lives after redecorating.” Her frown turned too quickly toward him. “That’s not actually true... I just... like to think it. The wiring’s completely fu... there’s no electricity in here yet, but I’ll run a cable from the garage.”

“Are you qualified to do that?”

William was not sure how to reply and pressed on into the passage once more. She retrieved her suitcase from the front door but he took it from her, the weight that twisted the handle making no impression on his arm. It was the sweep of staircase at the far end of the entrance hall and its lavish vinous carving that relieved her frown, her hand following the quartersawn balustrade as they ascended. They were confronted on the upper landing by the heroically-mounted head and shoulders of some giant caprine beast, crowned with horns that turned in spirals thicker than her calves. The same deep velvety green darkened the windowless ways leading away in either direction at the head of the stairs. He nodded toward the east.

“That end’s mine, Ed’s that way, and that’s technically a room, but the floor drops when you walk on it and I think there might be bees in that wall too...”

She glanced into the chamber he discussed as they passed by; footprints had entered and retreated, a portion of the floor lying undisturbed beneath a carpet of dust and windblown leaves. Toward the far wall the structures overhead admitted a view of the scilla-blue sky.

“It'll be nice when it’s finished.” she observed. The remark was received in a spirit of polite, if slightly blank, inquiry. "When you’ve done it up. Remodeled... isn't that what they call it here?" She laughed uncertainly. "The rain comes in back there... you'll have to do something." Susan lifted a hand to the strap of her bag. "This is your house, isn't it? You're not... squatting, or anything?"

William laughed.

"My brother paid cash money for it, croyez-le ou pas."

At the end of the central corridor a row of picture windows permitted a broad view of the garden and lit a narrow course of stairs into a gable. He allowed her to precede him into a petite garret apartment, its leaded panes casting storiated blocks of sunlight onto the oak bed. They were repeated in the dusty kitchenette, where a pine rack held a set of homely blue and white. She peered into the bathroom and found it half-filled with the belly of a footed tub; returning to the bedchamber, Susan lay her bag down on the mattress and turned toward her guide again. He had to stoop slightly with the angle of the ceiling; his size, framed in such vicinity, made her uneasy, and she looked down into the grounds. The verdant prospect moved her to a sigh that loosed the tension in her shoulders.

“That is such a lovely garden..." He smiled again in unreserved agreement as she reached out to tug a light cord. “Does this have electricity?” To his eye she projected strongly contradictory qualities, youth and sagacity, a self-containment that confused his initial assessment of her age and made him realise how inured he had become to its surgical effacement. His thoughts wandered, unbidden, along a tendril-shaded trail into more private speculation and he sank down in the Morris chair behind him, long white fingers spilling over the edge of its arms. Susan's uniform dug into her flesh along its side seams, loose hair curling on her collar in the heat cast by the window. “Accommodation’s included in my wages so I don’t pay rent, or any electric." she informed him gravely, relieved by his complaisant shrug. “Food is... it's meant to be negotiable..."

He shrugged again.

"You talked me into it."

"We can go over my duties if you like. Where should I start?” William gazed back at her dumbly. “Well then... what would you like me to call you?”

“William's fine.”

“Are you sure? It’s just that... most people find a formal title m... it would be more... professional...” she informed him, losing track of her spiel as his head tipped back against the wall, watching her lips move with a tranquil, almost somnolent gaze. She squeezed her own closed and began again. “I wouldn’t be offended, in fact I would prefer...”

“I would be offended.” he murmured. She shook her head.

“Mr Lamb, I...”

"William."

“Well... if there’s nothing in particular you’d like me to be getting on with, I’ll just start tidying up in here... are you sure there’s nothing else?”

“You seem sure there is.” he replied.

“I've been over here a while, and everyone seems to know exactly what everyone else should be doing.” she muttered, the observation renewing his smile.

“There probably is something, but... I do have a house guest...” he offered. “He’s gone off somewhere but he’ll be back, sometime... so don’t worry too much about... you know... peculiar strangers. I’ll let my brother know you're here. He will absolutely tell you what to do.” Easing himself out of the chair, he offered his hand again in confirmation of her engagement. “You won’t have to cook, we’re... what’s it called? Macrobiotic.”

“I’m not paid to, anyway. And I don’t do mouse traps or take out the rubbish. It’s in the contract.”

He received the news with the equanimity he had accorded the rest of her pronouncements, leading her to wish she had devised more.

“Do you think you'll be okay out here?” he asked. “It’s a long way from anywhere.”

“I'll be alright. I’m sort of sick of people.” Susan confessed. He shrugged, and turned toward the door.

“If you need anything, demandez juste. Je vis pour servir seulement. Er... parlez-vous français?" William added, gently hopeful.

"No, sorry."

"Oh well... with my roadkill anglais deal you must. If you need anything, just call down."

His bare feet made no sound as he departed, stooping once more at the doorframe and leaving a room that seemed much larger in his absence. She sat on the bed, reaching out to beat a puff of dust into the air around her, and fell to staring at the chair that he’d vacated.

CONTINUED NEXT WEEK

© céili o'keefe do not reproduce

RSS Feed

RSS Feed